On Digital Infrastructure: Cell Towers

A comprehensive primer on the macrocell (cell tower) industry

Why I care about digital infra

In the first lecture of CS106B (Stanford’s introductory CS class), Chris Gregg emphasized that abstractions are the most important concepts in computer science. Indeed abstractions give us superpowers and enable us to ship in days or weeks rather than months or years. It is however also deeply rewarding to unpeel abstractions, and understand how technology fundamentally works in both theory and practice.

In the technology sector, I see three primitives underlying more or less all advancements: energy, compute, and networking. The first two I’m probably neither smart nor patient enough to work on, but the latter has been an area of fascination for me. I won’t wax poetic, but there’s also something philosophically appealing about the connection between facilitating more seamless collaboration, and progress.

My objective, in my career and these memos is to understand these primitives, and subsequently improve them. Specifically, I’ve been researching digital infrastructure which refers to the hard assets like data centers, fiber networks, and cell towers that comprise the modern Internet.

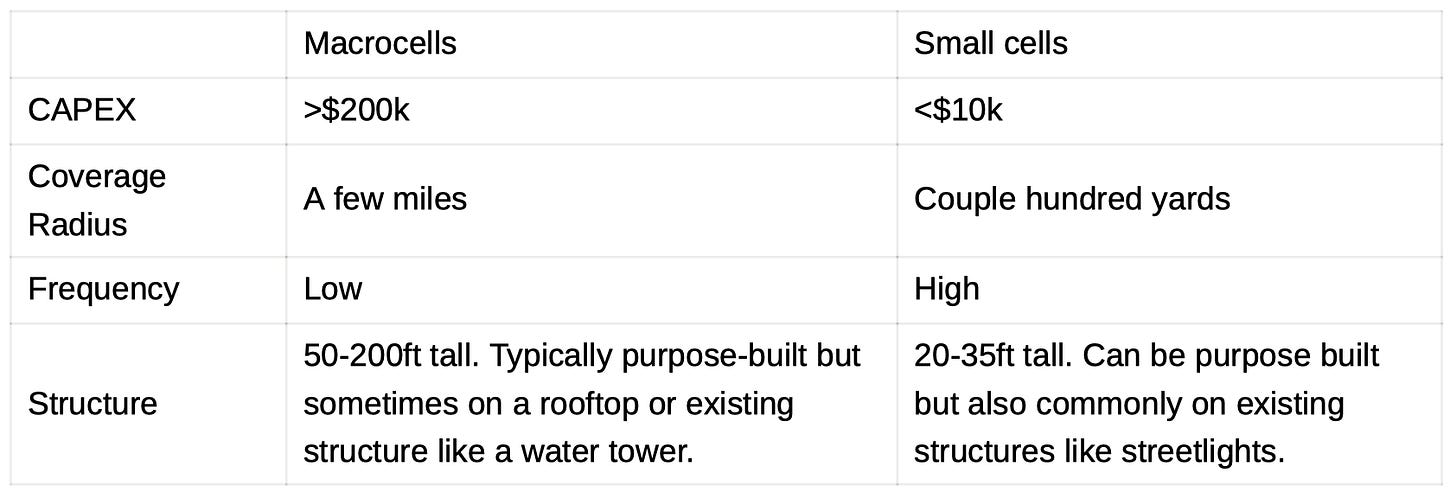

In this memo, I’ll be covering the cell tower industry — the industry jargon for which is a macrocell — which I’ve come to understand through conversations with extraordinarily generous people. I may briefly also touch upon small cells and fiber networks.

The protagonists

American Tower Corporation (AMT), SBA Communications (SBA), and Crown Castle International (CCI) are the three key players in the tower industry, each with its unique strategies and assets.

American Tower Corporation: AMT is the largest tower company globally, with a vast portfolio of more than 180,000 sites including significant acquisitions and investments in multiple international markets. Their primary strategy is to focus on owning and managing a diverse mix of assets, including towers, small cells, and distributed antenna systems (DAS).

SBA Communications: SBA is a leading independent owner and operator of wireless communication infrastructure, with a portfolio of approximately 32,000 sites across North and South America. SBA's strategy is to focus purely on macrocells and the American market — ≤15% of their revenues comes from international markets.

Crown Castle International: CCI has a diversified asset base with a portfolio of over 40,000 towers, more than 80,000 small cells, and approximately 80,000 route miles of fiber. Their strategy involves focusing on urban markets and investing heavily in small cells and fiber networks to support the growing demand for high-speed wireless connectivity and data consumption. CCI aims to capitalize on the increasing need for denser wireless networks, particularly with the rollout of 5G.

DigitalBridge Group (DBRG) also operates towers by way of its subsidiary Vertical Bridge. DBRG is a digital infrastructure fund that invests in and operates across several industry verticals including towers (over 9,000 macrocells), small cells, data centers, fiber, and edge infrastructure.

💡 Note that all these entities are publicly traded as Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), reflecting their underlying nature as a niche form of commercial real estate.

REITs are a type of corporate entity not subject to corporate income tax so long as they distribute at least 90% of their taxable income to shareholders as dividends.

A little industry history

The first tranche of wireless towers were built in the 1980s by the carriers themselves. There was no tower industry. The carriers were deploying their networks, and in order to deploy their networks, they needed suitable plots of land which they leased from local landowners. These early leases were 4 or 5-year leases with 5 automatic renewals and 2% escalators — essentially agreements lasting roughly 30 years through to around 2005.

💡 There were four US national carriers — or mobile network operators (MNOs) — at this point AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, and Sprint, and so four was effectively the maximum number of lessees one could get. Note that T-Mobile and Sprint since underwent a merger which closed in 2020 — more on this later.

Then along came land lease aggregators. The first aggregators were purely interested in financial engineering. If Bob the farmer was being paid $10k/year (picked an easy number for calculations, but $750-$3k/mo depending on location is ballpark accurate), they would offer Bob 10x cashflows/$120k upfront for the lease with the intention of securitizing a group of towers and then selling them off to an infrastructure fund or a tower company for 12 or 14x cash flows. A specialized tower industry had emerged at this point — American Tower Corporation, SBA Communications, and Crown Castle International — enabling carriers to focus on their core business while tower companies benefitted from economies of scale in leasing space on a single tower to multiple carriers.

Then aggregators become more savvy. While relatively unsophisticated landowners feared the threat of tower companies relocating their tower if not given favorable renewal rates, investors realized the landowners held more negotiating power than they recognized.

Carriers carefully choreograph their networks, and a move of even a few hundred yards may create coverage holes. Additionally, given the aesthetic pollution, local governments are reticent to permit towers structure to be built in close proximity (somewhat less prevalent in rural areas). One expert I spoke with very roughly estimated that ~70+% of towers today are in areas where it would be virtually impossible to build a new tower due to local regulations. Finally — not to belittle landowners by calling them unsophisticated — one must understand that the threat a carrier walks away and a multi-hundred-thousand-dollar payday (in many cases more money than the entire rest of the property is worth) goes to effectively zero is much scarier to a single small un-diversified actor than to an institutional aggregator playing this game across dozens or hundreds of sites.

The above, combined with the fact that in 48/50 states when a lease expires any structure on the land is considered a fixture and becomes the property of the landlord, presented a new opportunities for aggregators. Aggregators like Tristar sought to purchase (or get a permanent use easement for) the land under towers with (initially) less than 5 years remaining in their leases (including automatic renewals) and were well leased up (≥3 tenants). They could offer Bob 10-12x cash flows for the land, and in less than a decade, double the rent and have a property worth over 20x original cash flows.

Carriers thus began wising up and sought to extend their leases to ~35 years, or acquire the land underneath their towers. Carriers leveraged their lower cost of capital to push land prices to 16-18x cash flows, and began engaging landowners in lease extension or purchase discussions earlier with 5, 7, 10, and then 12 years remaining in the lease — with the threat of building a new tower being more credible the further they were from expiration. This competition from carriers was such that most aggregators eventually no longer found the business attractive with multiples somewhat stabilizing around 18x.

💡 Every tower must be registered with the FCC and FAA, you can search through them here — a useful tool for aggregators finding targets.

As a fun aside, some semblance of honor among thieves exists, since it wouldn’t be good for industry if prices were pushed up by AMT seeking to buy land underneath CCI’s towers and vice versa. It sometimes happens though, and to some degree is done knowing CCI owns some land under AMT’s towers, and so AMT might buy for the purposes of doing a trade down the road.

Finally, bringing us closer to present day, in the mid-2010s a series of deals were struck in which carriers leased the rights to a majority of the towers they still managed (with end-of-lease purchase options) to the tower companies — in part to fund bids in FCC spectrum auctions. Verizon sold its towers to American Tower, Sprint sold to SBA, while AT&T and T-Mobile sold to Crown Castle.

How to be a tower company

Search Rings

Most towers are built due to a carrier issuing a “search ring” based on a coverage hole or capacity constraint they’ve identified from internal data. A tower company will then find a plot of land matching the carrier’s objectives, and then build the tower (a “Build-to-Suit). So there’s no risk, as the tower company already has one “anchor tenant.” It’s not entirely top-down though. Tower companies also leverage coverage data from providers like M2 Catalyst to identify opportune locations and pitch the carriers to issue a search ring.

💡 With one tenant, tower operators earn ~3% return on capital, with two that’s ~10%, and with three it becomes ~20%. It can be a pretty good business!

Speculative Development

More rarely, a builder/operator will independently speculatively buy or lease, and then zone, land in areas they believe carriers have coverage holes or are likely to build out their networks (a “Zone-and-Hold”) and then promote those locations to the carriers. A few smaller players dabble exclusively in this space, each developing a handful or a dozen of towers per year. The major tower companies then typically acquire batches of these independent towers.

Tower pricing

The tower companies have “Master Lease Agreements” (MLAs) with the carriers which set ground rules covering the thousands of towers in their portfolio (hence the renewal of MLAs is a contentious time for stock prices). Notably, American Tower and Crown Castle’s MLAs include pre-agreed pricing whereas SBA’s does not. With pre-agreed pricing, operators don’t make as much as they could in prime locations, but also make more than they otherwise would on less-desirable locations, so it evens out.

Small Cells and Fiber

The fiber industry is one that deserves lengthy coverage in and of itself. For the purposes of this article, I’m going to focus on how fiber relates to small cells with the two being complementary — hence why Crown Castle is investing heavily in both, while American Tower has opted to move in an entirely different direction (expanding macro cell presence to international markets). As briefly touched upon at the very top, small cells offer a shorter radius of coverage and are much cheaper to build than macro cells. The operational complexity given the quantity of sites, and availability of alternatives, however make this a much lower-margin business than macro cells.

In fact, municipalities will typically lease space on existing utility poles for smalls cells at ~$20/month. 70-80% of the cost in building a small cell however is actually in building out the fiber to the small cell site. For Crown Castle, the buildout of small cells is thus in part simply to subsidize the expansion of their fiber backbone, and thus a mechanism to enable entry into other fiber-related businesses.

Industry trends

The Radio Access Network

The Radio Access Network (RAN) refers to the hardware and software stack that connects devices to the core network. In traditional RAN, each cell site has an antenna at the top of the tower, a radio installed right below the antenna, and a baseband unit which is essentially the brains of the RAN (hardware + software) sitting in an onsite weatherproof and temperature-controlled cabinet (that’s the little shack you might see at a cell site). Everything above from the antenna to the baseband software would have to be purchased from one of a few vendors: Ericsson, Nokia, or Huawei. And an operator can’t mix and match because an Ericsson radio can’t talk to a Nokia or Huawei baseband — everything was built to proprietary specifications.

Virtualized RAN

Virtualized RAN (V-RAN) was the first step in moving away from the hardware-centric model by virtualizing the networking layer through software-defined networking (SDN). V-RAN meant baseband software could now run on commodity hardware/servers, enabling greater flexibility and cost-savings. Network architecture can be adjusted on the fly, and the onsite cabinet became redundant as tower radios simply relays the data over fiber for processing by software running in a datacenter miles away — perhaps in a public cloud. While previously each tower needed to be installed with sufficient baseband hardware/compute (that also periodically required someone to drive to the site for maintenance or repairs) in its cabinet to handle peak traffic hours, now compute can be easily scaled up or down in the cloud to enable savings during off-peak hours.

Open RAN

Open RAN (O-RAN) is a further extension that aims to standardize all components of the RAN stack, such that operators can mix and match hardware and software from any vendor. Incumbent vendors obviously criticize O-RAN as being untested, however Rakuten (an Amazon-like Japanese conglomerate that launched a carrier business in 2020) is now serving over three million users (and mostly in dense urban areas like Tokyo) so the technology has proven itself to be able to stand up to heavy traffic.

Rakuten is now attempting to commercialize its O-RAN competencies via the Rakuten Communications Platform (RCP) to create a one-stop shop for other budding MNOs (or even non-telco companies) to stand up an O-RAN network with each layer of the stack being configurable akin to how you might option a car — the venture is analogous to how Amazon created AWS to commercialize their datacenter expertise. Critics however point out that the RCP universe as it currently stands (since it still doesn’t support many vendors) — or vendors like Mavenir marketing “end-to-end” O-RAN — are in opposition to the open-ended spirit of O-RAN.

Dish Network

These developments in RAN are relevant to the tower industry because as touched upon earlier, it greatly lowers the cost of entry for new MNOs — non-telcos might also want to stand up a private company network, i.e. at a Siemens industrial site — with 30-40% CAPEX savings and continual 30% OPEX savings.

💡 We have to make a brief aside here to touch upon the T-Mobile and Sprint merger. In 2018 the two companies agreed to merge such that the combined entity would have comparable market share to Verizon and AT&T and as such would allow have better competitive footing but the FCC and DOJ were nevertheless also concerned about the anticompetitive impact of going from four to three national carriers.

Dish Network then raised its hand to play in the space given that it already owned some spectrum, and already competed in the TV broadcasting part of the ecosystem (as you may know, connectivity services are often bundled). Thus the merger was approved, with conditions including that T-Mobile/Sprint sell some spectrum, roaming agreements, and Boost Mobile (a subscriber base) to Dish in order to bootstrap a new national MNO.

From a tower operator’s perspective the T-Mobile/Sprint merger meant the maximum number of tenants they could lease to at a single site effectively went down from four to three. It was forecasted that the merger would cause the combined entity to shut down 35,000 towers due to overlapping coverage, but as Dish rolls out their network the hope is that it will return to four. The ability to more easily build a network or add equipment thanks to O-RAN is also generally viewed as incrementally positive by tower operators.

What’s notable about Dish is that as a new “greenfield” operator without legacy hardware, they’re more incentivized to be the first major American O-RAN network and have indeed been working closely with Rakuten in their deployment. Some speculate that Dish’s end goal is to prove the concept and then sell the wireless business to a bigger potential entrant like Comcast, but their progress has been steady and regulators are keen to have four national carriers. Meanwhile, the other players are monitoring Dish’s O-RAN deployment closely as they continue to roll out new 5G networks.

5G and the Edge

The tower business is somewhat cyclical, with a new generation of networks coming online every decade or so. Historically, from 1G to 4G the increasing size of equipment has been a justification for tower operators to hike prices. This is actually no longer the case with 5G equipment often being smaller, but the new technology has created other new opportunities.

For one, any rollout of new technology is incremental, 5G has been deployed today to the densest markets but its rollout isn’t going to be complete nationwide for years to come, it’ll probably take around a decade. In the meantime carriers will co-locate 4G and 5G equipment on towers with more equipment meaning more revenue opportunities — at least for some operators. When T-Mobile and AT&T sold their towers to Crown Castle, and when Verizon sold its towers to American Tower, they reserved space for 5G equipment. SBA meanwhile didn’t acquire any towers from carriers, so they’ll be able to extract more money from carriers.

The increased bandwidth of 5G is enabled by using higher frequencies, which comes at the cost of reduced coverage radiuses. In the long term this is going to drive demand for new macro towers, but as a first step carriers are one-for-one replacing their legacy equipment on existing sites. And their next focus will likely be sites where existing base structures like water towers or rooftops enable cost-effective deployment.

Beyond higher bandwidth, two other promises of 5G are ultra-low latency and high reliability. While the baseband units are disappearing, tower operators are now building edge data centers in shipping containers in the vicinity of towers, or in the basements of office buildings, to support these applications. A request from a self-driving car in San Francisco for example may be sent to the nearest tower, handled onsite by an edge datacenter (i.e. doing ML inference), and receive a result back much sooner than if the request were routed to a regional datacenter in Oregon. Tower operators essentially have an opportunity to become specialized high-performance/low-latency cloud providers.

Miscellaneous

Distributed Antenna Systems (DAS)

DAS is a related market in which the tower operators play, alongside Boingo Wireless which is one of the more dominant players. The goal of DAS is to ensure sufficient cellular coverage and capacity in key indoor spaces such as airports, stadiums, and hospitals, which they achieve by installing essentially small indoor radios throughout the building.

During construction (but also available as a retrofit) property developers will partner with a DAS provider to install backbone fiber for the network, and then, much like with towers, lease rights to install DAS radios to the various network operators — the more the better — and with an anchor tenant already lined up. This initial CAPEX/build-out of the network can be financed by a mix of players, including the anchor tenant/carrier, the DAS provider, or the venue owner — with revenues from the system shared between the DAS provider and venue owner.

💡 Intuitive, but worth clarifying: A lack of coverage is when you have no bars of signal. A lack of capacity is when you have full bars and yet sites won’t load. DAS can help solve both — in an underground parking garage it’s providing coverage, in a stadium on game night, it’s backfilling capacity.

On the face of it, investing hundreds of thousands into improving service across such little square footage seems silly, however one can speculate what the carrier’s data science teams have concluded about the customer experience:

Imagine you’ve just taken a crisp photo of Tom Brady making the game-winning pass and open Instagram, only for the upload to fail on AT&T because you either have no bars or — worse yet full bars and yet the shitty network still doesn't work. You then turn to your friend in frustration, only to see his photo upload seamlessly on Verizon.

Repeat for a couple games, and AT&T just lost tens of thousands of fans per quarter, each of whom were paying $40-80 per month. Pricing and network quality is by and large equal across major carriers, it’s the long tail of locations and situations where customer loyalty is won and lost.

A notable sideline to make here however is that carriers typically have more leverage when negotiating MLAs for DAS as opposed to macro cells. While macro cells, as touched upon previously, are hard to substitute, an alternative to DAS for carriers is tweaking their macro network outside venues to ensure sufficient coverage and capacity given average traffic from that venue.

Akin to how carriers increasingly bundle cell plans with home internet and entertainment, tower operators are ultimately also trying to bundle more and more services, from placement on DAS, to small cells, to macro cells in their agreements with carriers.

Private 5G Networks

Installing fiber backbone in a building, only to still require each carrier to install their own DAS radios across the building seems inefficient. Enter private 5G networks. Companies like Celona build out full “private 5G” networks — with small cells and/or DAS — capable of servicing any customer regardless of their primary carrier. MNOs would essentially pay to be MVNOs in a specific building to gain DAS-like service without having to touch any of the physical infrastructure.

💡 Mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs) don’t own physical infrastructure, instead they pay to piggyback off the an MNO’s network. Popular MVNOs include Mint Mobile, Google Fi, and Cricket.

Private 5G networks however aren’t just a more infrastructure-light replacement for DAS. As their name implies, they can also be set up simply as private networks, perhaps at industrial sites like warehouses, docks, or mines where there’s either weak coverage, or there’s a need for ultra-high density and reliability as required by automated machinery and IoT devices.